Sappho and the Queer Imagination

Sappho of Lesbos. Painting by John William Godward.

Sappho, the infamous Greek poet whose best known for her homoerotic poetry, is a woman shrouded in mystery. Most of her poems and songs were lost throughout the centuries, and all that remains are a small collection of fragments. Historians, scholars, and readers fill in the gaps for her, placing a few pieces in a puzzle that seems to dissolve into obscurity.

Sappho’s legacy is largely in her name, as the word “sapphic” was used to describe love between women at the turn of the 20th century. Prior to that time, however, lesbian was used to described anything derived from the island (i.e. lesbian wine simply meant wine from Lesbos). We don't see the term Lesbianism until around 1870, when it was used in a medical dictionary to pathologize romantic love between women.

Queer figures in history often feel mythological. Even reading about Sappho's fragmented history, what we know about her biography is so limited that it collapses into speculation. As you can see below, Sappho's one-lined poems are numbered and joined together like the lyrical jumble of a found object poem.

Excerpt from Poems of Sappho.

The idea of the found object poem, defined as a poem comprised of parts from other texts such as journals, other poems, newspapers, novels, ect, reflects the historical lesbian consciousness. What do we have save scrapes of biography and medicalized journals detailing queer abnormality?

Due to the historical inaccessibility of language and writing (Sappho was an upper-class woman who had access to education), our accounts of queerness are not only far and few but often limited to people of wealth and status.

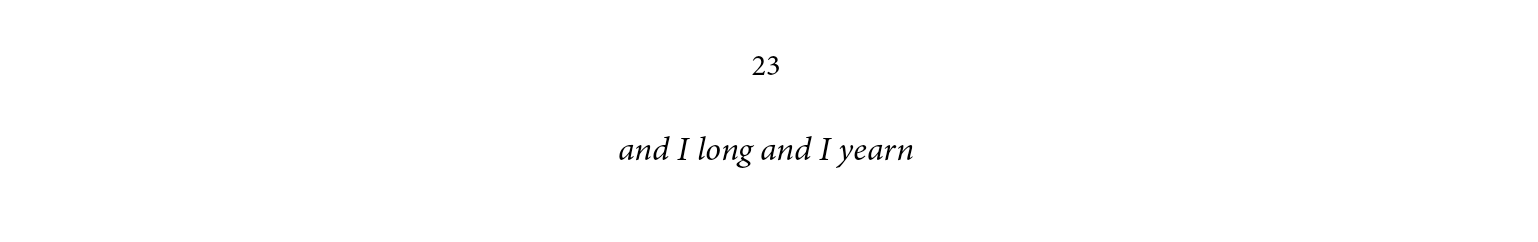

The new HBO period drama, Gentleman Jack, is inspired by the coded journals of Anne Lister, a wealthy land-owning lesbian who lived in 19th century England. Lister is important in lesbian history because she wrote explicitly about the sexual encounters she had with women, exemplified by the excerpt below.

From the diaries of Anne Lister, read more here.

In Emily Nussbaum's essay "Chick Magnets on “Gentleman Jack” and “Killing Eve,”" she writes: "Lister was a gender-disrupting trailblazer, who recorded experiences that society refused to admit existed. (Male homosexuality was outlawed; the female version was unimaginable.)"

In this context, Anne Lister's explicitness a blessing, as her society's imagination couldn't even fathom her existence. Sally Wrainwright, creator of Gentleman Jack, mentions how Anne Lister is "the first person in history who talked really clearly about gay lesbian sex. Prior to her diaries being decoded, people just didn’t believe that women had sex at this time. They thought women who had close relationships, they were romantic friendships rather than the fact that they were actually getting down and having a good time.”

Lister’s detailed accounts of her sexual encounters are starkly contrasted to Sappho's whimsical and poetic musings of her love for women. Of course, this can be explained by the drastically differing time periods they both lived and wrote in and even reflect their personalities. But both are sacred, as their work exemplifies the various forms that queer expression can and did take.

In an introduction to a book of Sappho's poems, writer and translator John Maxwell Edmonds mentions Sappho's relationship with the girls she allegedly instructed in her school:

"Now these girls were more than pupils to Sappho; they were friends, and, some of them, bosom-friends. And in these cases, as sometimes will happen with highly emotional natures, the friendship could more fitly be described as love."

This was written in 1921, which explains some of the language. But even still, it's cringe-worthy to read (bosom-friends???) because it presents lesbian love as a volatile whim.

Women's desire for one another is still characterized as a girlish and feverish drive thought to wear itself out by adulthood. America's patriarchal and homophobic lens simultaneously hyper-sexualizes the physical connection between lesbians while dismissing their capacity for love.

In an article about Sappho on Ancient History Encyclopedia, the author writes about scholars that advise against seeing her poems as biographical, given the possibility that Sappho could be writing from perspectives not her own. He also suggests: "While it is possible, then, that Sappho was a lesbian, it is equally possible that she wrote on many subjects but that her works expressing lesbian love are the ones that have survived most intact."

So little is actually known about her, and the lost pieces of her work allow for both misunderstanding and the opportunity to insert one's own interpretations.

Excerpt from Poems of Sappho.

From a heterosexual perspective, it'd be easy to overlook Sappho's romantic poetry towards women as odes to the goddesses, or even entertain the possibility she was writing from the perspective of a man. Isn't history's ambiguous understanding of Sappho’s work convenient for the status quo?

Sappho's ascent into mythology is mostly because so much about her is unknown. And this ambiguity is the birthplace of the queer imagination.

With so little reflections and representations of queerness, the gays are forced to improvise. We create our own stories, weaving our own narratives alongside heterosexual love stories. As a teenager, I'd write fan-fiction of my favorite movies and books but with characters whose desires resembled my own.

This creative, revisionist approach to history sees facts are unreliable. The logic of documentation is rendered obsolete. Does this make our interpretations any less legitimate? Absolutely not. For centuries, the history of the world has been controlled by the Western man. The off-chance that queerness and gender-deviance appeared in the timeline of the past could have easily been erased.

We see the power dynamics even in Anne Lister's journals. She's rich, white, and English who inherited property from her family. Her wealth was generational. In some ways, her ability to be educated and write about her lesbian experiences is born from wealth disparity and colonialism.

It's such an agonizing contradiction. One that appears again and again throughout history and into the present day. Those in power, those with power are the ones who control the narrative. Or at least, have access to it.

Excerpt from Poems of Sappho.

While historical representations of queerness matter, they are hard to come by. Imaginatively inserting our narratives into a timeline that refuses our existence is often our only option to see ourselves in the past. If people want to see Sappho's work as queer, then so be it. The heterosexual world commands the legal, social, and cultural realms of our lives. It tries to manipulate our thoughts, make us doubt our instincts. It threatens to overwhelm our minds with internalized images of the "ideal relationship" and a "normal" way of being.

And yet, queer people inherently aren't and can't be what heteropatriarchy wants us to be. I am reminded of Audre Lorde's exploration of the erotic, a concept she describes as "an assertion of the lifeforce of women; of that creative energy empowered, the knowledge and use of which we are now reclaiming in our language, our history, our dancing, our loving, our work, our lives."

She goes on to explain the many ways heteropatriarchy has abused her interpretation of the erotic in her essay "Uses of the Erotic:"

"The erotic has often been misnamed by men and used against women. It has been made into the confused, the trivial, the psychotic, the plasticized sensation. For this reason, we have often turned away from the exploration and consideration of the erotic as a source of power and information, confusing it with its opposite, the pornographic. But pornography is a direct denial of the power of the erotic, for it represents the suppression of true feeling. Pornography emphasizes sensation without feeling."

To me, imagination is part of erotic power. Creative visualization is a form of witchcraft. If pornography is the erotic's opposite, then hyper-sexual representations of queer connection is the opposite to our imaginative, feeling-orientated understanding of pleasure and love. Queer people inserting their desires and narratives in the gaps throughout history is sorcery.

In Candace's Walsh essay "The Queer Gaze and the Ineffable in THE PRICE OF SALT," she examines the ways Patricia Highsmith describes queer desire in her novel The Price of Salt.

Walsh writes: "The first time Therese sees Carol, she notes, “She was tall and fair, her long figure graceful in the loose fur coat that she held open with a hand on her waist.” Carol’s form is described from head to toe—“tall,” with a “long figure.” She’s both dynamic in the scene, and whole. This contrasts with a style of description that might depict a character in respect to the parts of her body, zooming in on breasts, waist, or legs, descriptions that emphasize parts over whole."

Even if you never read The Price of Salt, it's evident that the sexual tension between Therese and Carol is not pornographic, it’s erotic. As Candace Walsh points out, Highsmith’s description of Carol isn’t stagnant or fragmented, but dynamic and reflective of the various pieces that make up an entire person.

Heterosexuality characterizes queerness as hypersexual because it's seen as a deviance from sex between a woman and a man, the puritanical union which results in reproduction. Queer sex doesn't create a product (although this isn’t always the case). Queerness is therefore, unproductive in capitalist terms and exists solely for the pornographic.

This couldn't be further from the truth. Queerness is productive, but in capitalism’s terms. Being queer is understanding love in its infinite forms, allowing it to manifest through feelings. It breathes life into sexual encounters, but this isn't the only form it takes. Queerness is not simply an action, something we do, but a state of being. Of existing beyond society-imposed limitations.

The first time Therese and Carol have sex, Highsmith uses the metaphor of the arrow to describe an orgasm. It's so subtle that I had to reread the passage, and yet the image is so ripe with eroticism that I'm reminded of another line from Audre Lorde's essay: "To share the power of each other's feelings is different from using another's feelings as we would use a kleenex."

Excerpt from The Price of Salt by Patricia Highsmith.

While writing this essay, I've been thinking about the implications of the phrase "Love is love." It's often used to remind the heterosexual institution that love between queer individuals is no different than love between straight people. In some ways, this is true. Love is not gendered, nor does it ascribe to strict binaric guidelines. But to me, queer love is not the same as straight love.

Queer love is love infused with feelings of impossibility. Queer love was first born of the imagination, before it was seen. It began with a feeling, rather than an image. Queer love is eroticism in the sense that it doesn't prioritize sensation over feeling or vice versa. It's a union of tenderness and fear, anxiety and euphoria.

Once Therese and Carol realize their love has consequences, Therese thinks: “How is it possible to be afraid and in love…The two things did not go together." And yet queer individuals are forced to exist between these two opposing emotions.

Queerness is so otherized by heterosexuality that even its essence becomes distant and unfamiliar, too different to synthesize with the straight reality. This is arbitrary. Even my feelings about queer love existing on an opposing plan is arbitrary. It doesn't have to be like this, yet heteropatriarchy insists that it does.

This is why the queer creative revisionist process of history is so important. History shouldn't be so straight, with so many holes and gaps that leave out vital timelines. Yet it is. So I'm going to keep thinking of Sappho as a woman-loving, erotic-weaving poet, no matter if her queerness can never be proven.

Cassidy Scanlon is a Capricorn poet and witch who uses her artistic gifts as a channel for healing herself and others. She writes poetry and CNF about mental health, astrology, queer love, pop culture representation, and how social structures shape our perceptions of history and mythology. When she’s not writing, she can be found petting the local stray cats, exploring the swamps of Florida, reading 5 books at a time, and unwinding with her Leo girlfriend.

You can visit her astrology blog Mercurial Musings and explore more of her publications on her website.