Revisiting Adrienne Rich’s "Twenty-One Love Poems"

Published in 1977, Adrienne Rich’s Twenty-One Love Poems was one of her first books that addressed lesbian identity and desire. This revelatory context is felt throughout the work, as she details the tender and painful experiences of a lesbian relationship.

I discovered this book a few years back in Córdoba, Argentina, where I was visiting a boyfriend who loved independent bookstores as much as I did. At the time, I struggled to reconcile my queerness and my relationship with a straight man, and this manifested in my fixation with lesbian feminist literature.

Veintiún poemas de amor was a small sliver in a pile of books, but the familiarity of Rich’s name convinced my hand to pull it from the shelf. Published by the small press Postales Japonesas and translated by Sandra Toro, each page features the English version of the poems and a Spanish translation.

Later that day, my partner and I alternated reading each of the poems, mine in English, his in Spanish. I wanted to hear them spoken in a different language than what Adrienne intended, curious to discover if they had the same effect as reading the work. Although he sounded beautiful, I couldn’t help but be disappointed.

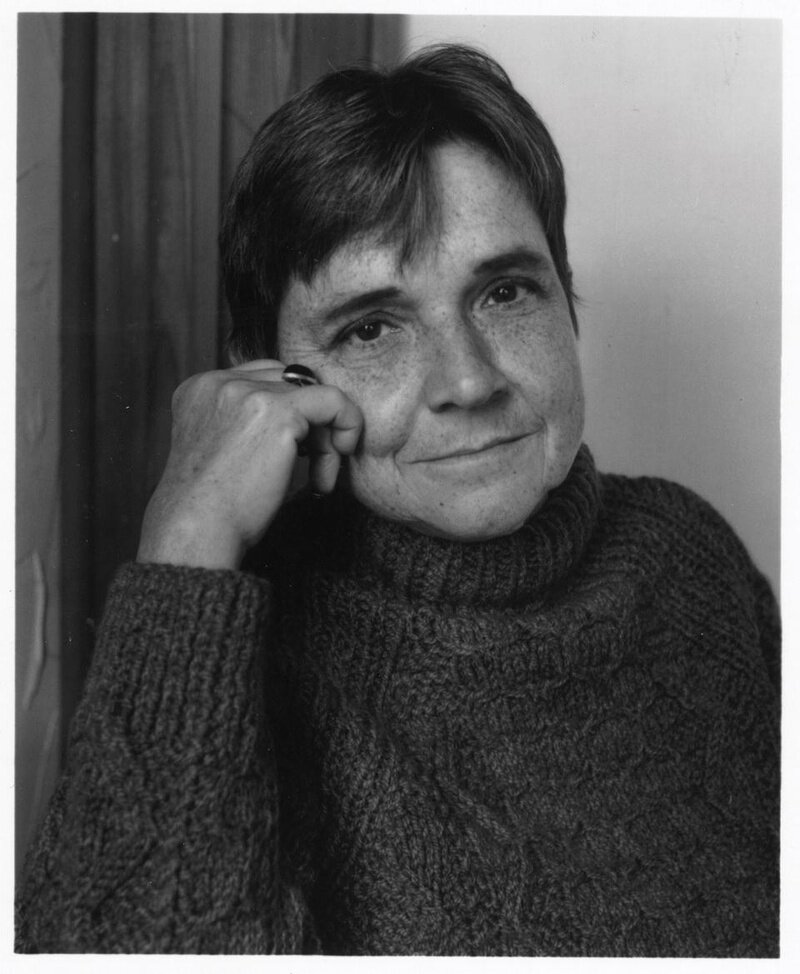

image via Google

The ache and longing was lost in translation; his voice seemed exist on a different plane. It was alienating, clutching at a part of my identity that felt nonexistent in my present circumstances. I wasn’t experiencing bi-erasure, which often feels like oscillating between an impossible dichotomy. This was different; my love for women was a lake frozen over, and I was trying to break the ice with a pen.

In the fourth poem of the collection, where Adrienne addresses the lack of lesbian and female experiences in literature, she writes:

“…we still have to stare into the absence

of men who would not, women who could not, speak

to our life–this still unexcavated hole

called civilization, this act of translation, this half-world.”

This half-world felt like a room of mirrors, where I saw reflections of myself everywhere, but only when I stepped inside it. These poems acted like a count-down to my break-up and reawakening to my queerness. I began to see my love of women everywhere, even in objects and places that weren’t explicitly “female.” Rocks, buildings, the awnings of trees spoke to me in whispers, reminding me of who I was. The eleventh poem of the collection reveals the way our external world acts as an echo of our interior lives. It opens with the lines:

“Every peak is a crater. This is the law of volcanoes,

making them eternally and visibly female.”

Twenty-One Love Poems queers the famous work by Chilean poet Pablo Neruda, Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair. Written in 1924 when he was only 19-years-old, the book was controversial due to its frank depictions of sexual content. Almost a hundred years after its publication, it remains widely read and purchased.

I was aware of Neruda, but not enough to understand or care about his work. When researching for this piece, I read through Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair. His poetic portrayals of sex made me uncomfortable, as his metaphors were lewd and painfully tacky (i.e. “Body of skin, of moss, of firm and thirsty milk!”). The first poem in his collection is called “Body of a Woman,” and includes the stanza:

“I was lonely as a tunnel. Birds flew from me.

And night invaded me with her powerful army.

To survive I forged you like a weapon,

like an arrow for my bow, or a stone for my sling.”

While reading his poems, I discovered a pattern of violence when describing love and desire. Neruda’s poem “I Have Gone Marking” begins up with the line: “I have gone marking the atlas of your body with crosses of fire.”

I asked myself: Is this what men find erotic? The visceral experience of weaponizing a woman’s body for their own protection and pleasure? Patriarchy created a system that weaves intimacy with violence, to the point where one is indistinguishable without the other. These images flowed through Neruda’s consciousness as he wrote, planted by the repetitive models of heterosexual coupling.

His descriptions of pleasure are equally reflective of these socialized patterns. In his poem “Drunk with Pines,” he writes:

“Hardened by passions, I go mounted on my one wave,

lunar, solar, burning and cold, all at once,

becalmed in the throat of the fortunate isles

that are white and sweet as cool hips.”

Is this the kind of writing that impacts our world? Pablo Neruda’s Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair is one of the best-selling poetry books in the Spanish language. I wonder, what would the world look like if Adrienne Rich’s work had the same impact, if women-loving eroticism could alter the male-centric model of human sexuality?

In her essay “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power,” Audre Lorde states:

“The erotic has often been misnamed by men and used against women. It has been made into the confused, the trivial, the psychotic, the plasticized sensation. For this reason, we have often turned away from the exploration and consideration of the erotic as a source of power and information, confusing it with its opposite, the pornographic. But pornography is a direct denial of the power of the erotic, for it represents the suppression of true feeling. Pornography emphasizes sensation without feeling.”

image via Google

This articulation of eroticism, especially within images evoked through writing, is what runs through my head when I read Pablo’s work. Men are obsessed with the “universality” of their literary canon, asserting that women’s writing is so obviously female and esoteric. The irony makes me laugh; for when men write about eroticism and desire, it’s so clearly rooted in their own preoccupations and sexual experiences.

Meanwhile, Adrienne Rich embraces the lesbian perspective as a subjective, personal experience. She writes about the limitations placed on her sexuality by a heterosexist society and how she struggles to live openly in a world that forces people like her to remain closeted. Her eroticism is infused with feeling, not purely sensation. It’s undeniably lesbian, and this deliberate focal point is what makes it impactful.

In my favorite poem, the second one of the collection, she writes:

“…I dreamed you were a poem,

I say, a poem I wanted to show someone…

and I laugh and fall dreaming again

of the desire to show you to everyone I love,

to move openly together

in the pull of gravity, which is not simple…”

I think of how gravity is taken for granted, how we are all bound by an invisible force that makes life possible. Women who love women gravitate to one another by energy that cannot be explained. We use language to describe love, desire, and romance, but it remains inadequate in the face of feeling. Yet despite this, lesbian writers continue to write. If only to capture a small, inconsistent fragment of a narrative that exists beyond words.

image via Google

Cassidy Scanlon is a Capricorn poet and witch who uses her artistic gifts as a channel for healing herself and others. She writes poetry and CNF about mental health, astrology, queer love, pop culture representation, and how social structures shape our perceptions of history and mythology. When she’s not writing, she can be found petting the local stray cats, exploring the swamps of Florida, reading 5 books at a time, and unwinding with her Leo girlfriend.

You can visit her astrology blog Mercurial Musings and explore more of her publications on her website.